If you know Frida Kahlo, you probably have one particular painting that pops into your head when you hear, see, or speak her name.

She is fierce, broken, loving, warm, austere, harsh, real, and strong.

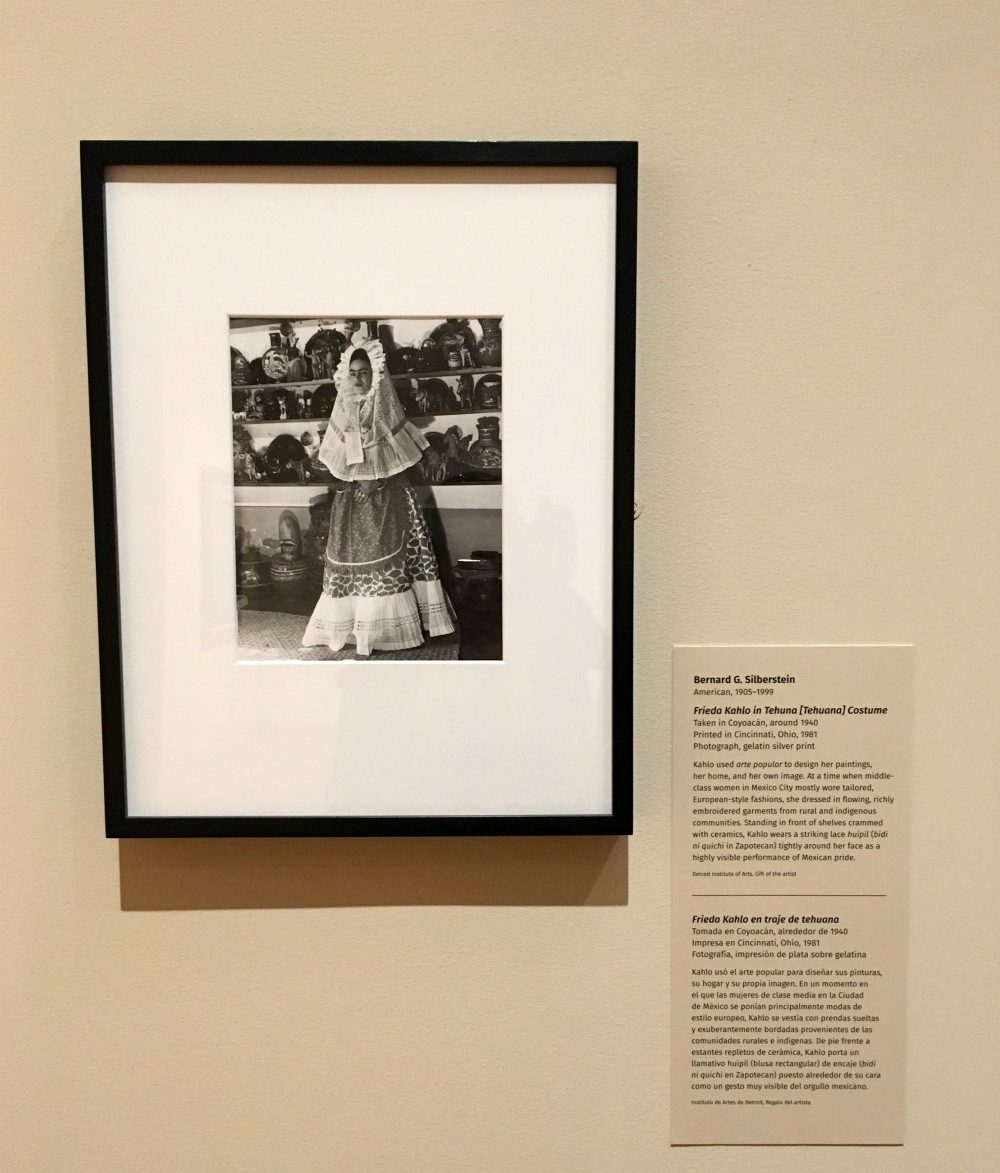

Frieda Kahlo in Tehuna Costume, Bernard Silberstein, 1940

Frieda Kahlo in Tehuna Costume, Bernard Silberstein, 1940

And I say 'is' because I see so much life and truth in her paintings that I believe parts of her are living in her artwork (something that can be said for a lot of art — or at least works that really evoke and carry emotion across time).

Still Life with Parrot, anonymous Mexican artist, mid-19th century

Still Life with Parrot, anonymous Mexican artist, mid-19th century

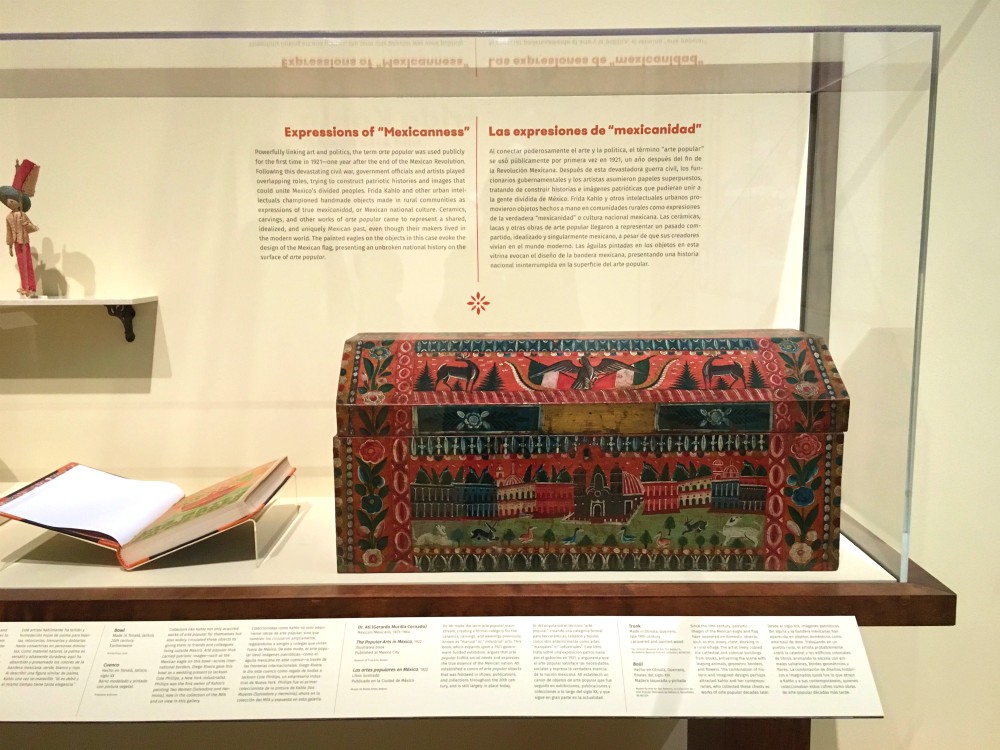

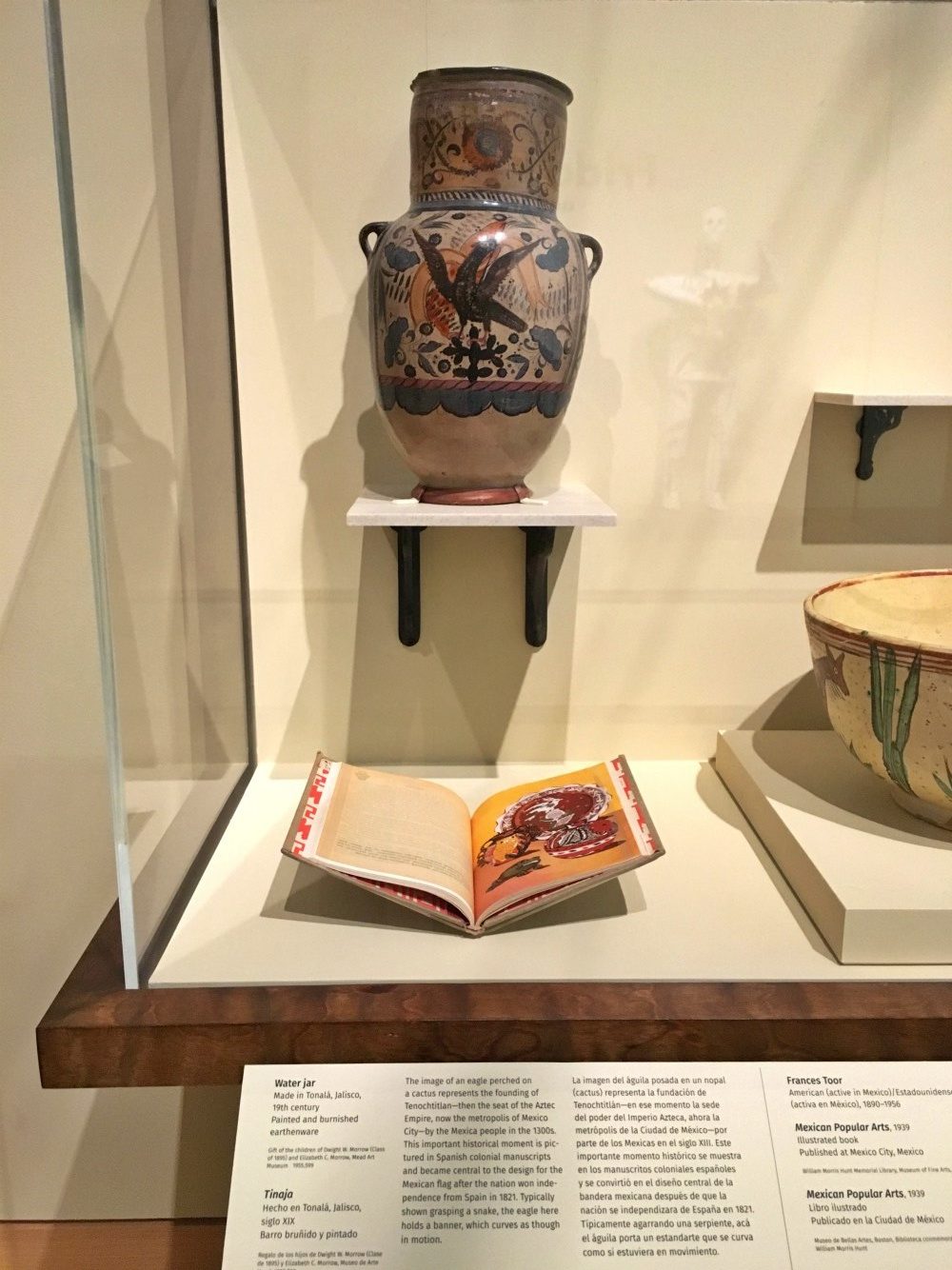

The MFA Boston's Frida Kahlo and Arte Popular exhibit transports you back to her home in Mexico City, displaying a few of her paintings amidst several rooms of the objects and artworks she personally collected.

Whistle and Mescalero, made in San Bartolo Coyotepec, 1930s

Whistle and Mescalero, made in San Bartolo Coyotepec, 1930s

Self- Portrait with Hummingbird and Thorn Necklace, 1940

Self- Portrait with Hummingbird and Thorn Necklace, 1940

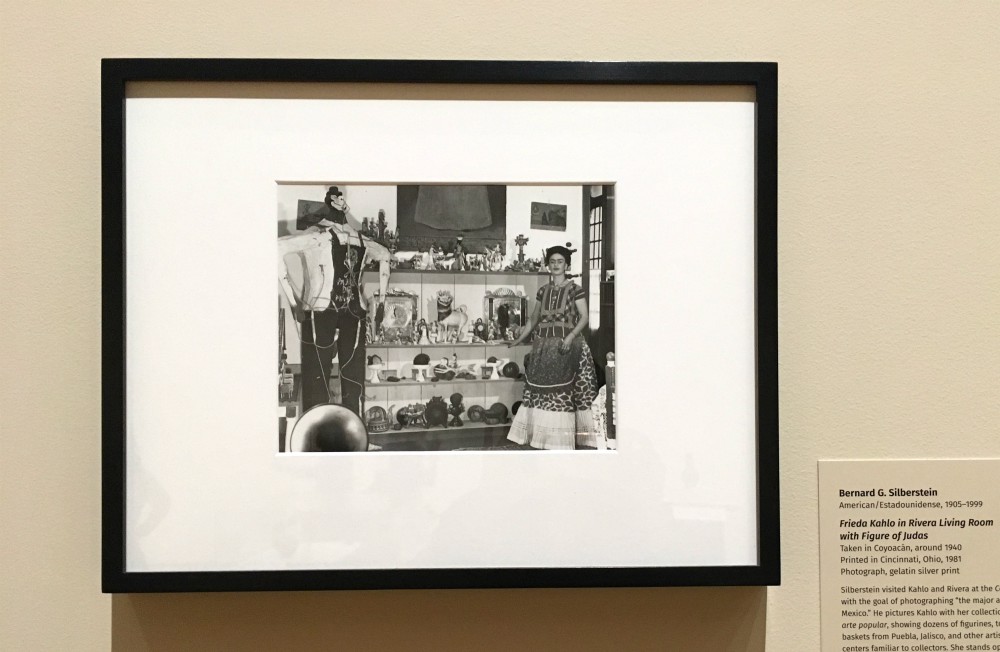

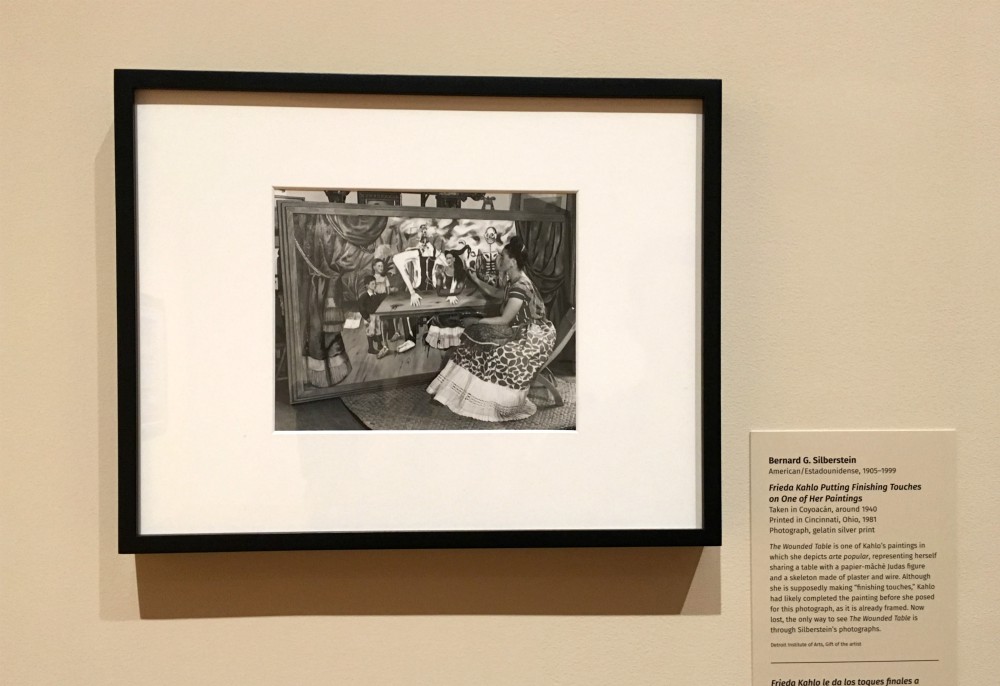

As evidenced in her dress from photos we have, and the themes, and scene sequences rendered in her paintings — Kahlo's love of her country's folkart and heritage is sincere and authentically included in her work.

Frieda Kahlo in Rivera Living Room with Figure of Judas, Bernard Silberstein, 1940

Frieda Kahlo in Rivera Living Room with Figure of Judas, Bernard Silberstein, 1940

Frieda Kahlo Putting Finishing Touches on One of her Paintings, Bernard Silberstein, 1940s

Frieda Kahlo Putting Finishing Touches on One of her Paintings, Bernard Silberstein, 1940s

For throwing her whole life and energy into the modernist movement and artistic circles of the early 20th century, its a wonder she wanted to preserve so much history in her paintings.

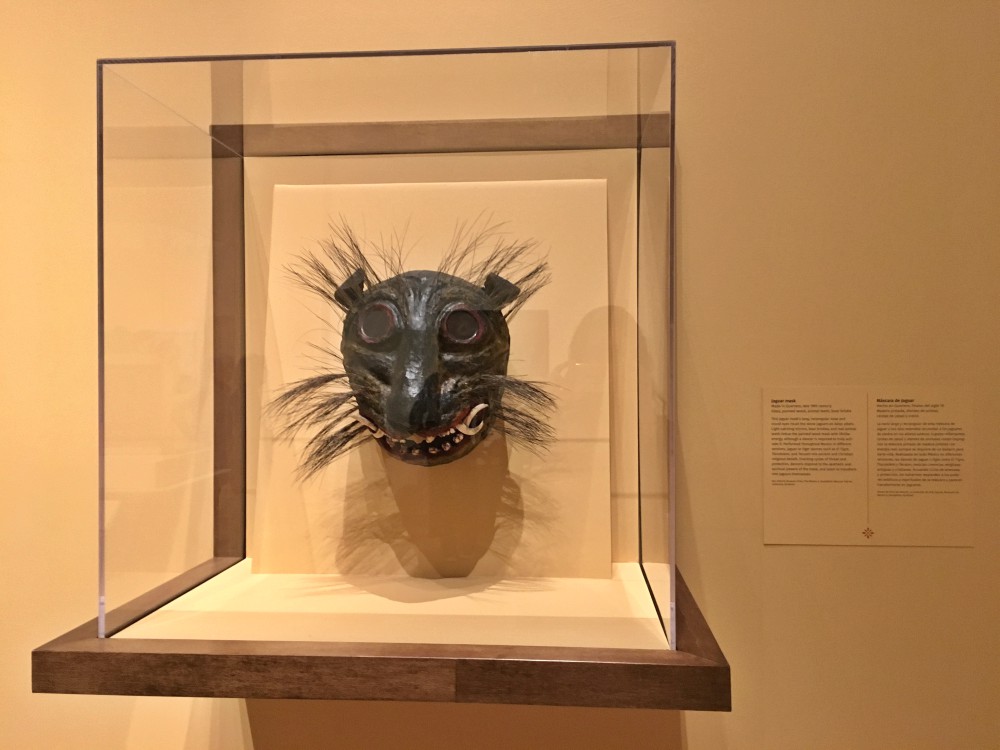

Wandering the galleries you come across textiles, child toys, and animal sculptures that were obvious inspirations for details in her artwork.

Jaguar mask, made in Guerrero, 19th century

Jaguar mask, made in Guerrero, 19th century

One section of the MFA's wall text includes this quote: 'I really love things, life, and people...I'm not afraid of death, but want to live.'

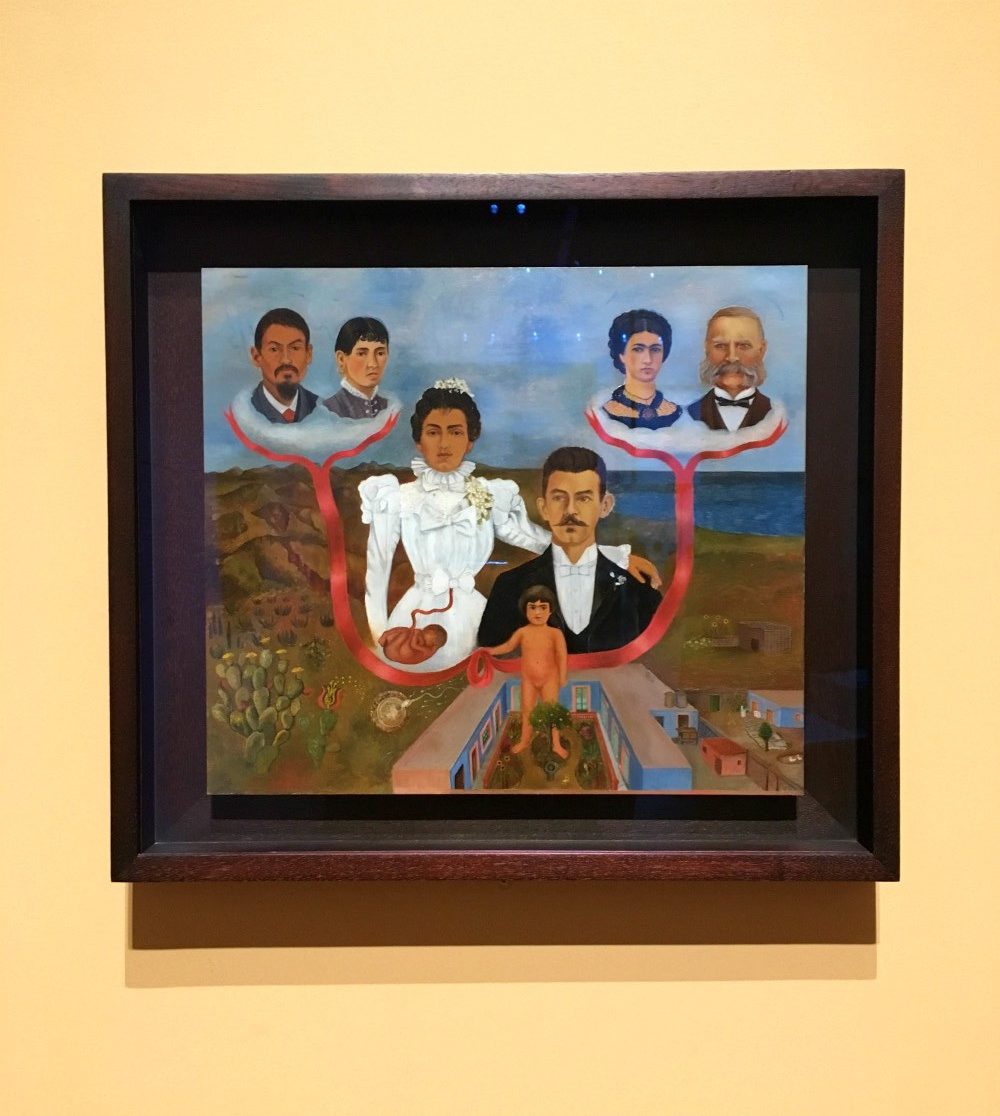

My Grandparents, Parents, and I (Family Tree), 1936

My Grandparents, Parents, and I (Family Tree), 1936

Tree of Life, made in Izucar, mid-20th century

Tree of Life, made in Izucar, mid-20th century

Life is present in everything in this exhibit, and one can suppose that she had such a collection of objects to give a new life to things — the many many things — she had lost in her life, a mark of her brave optimism.

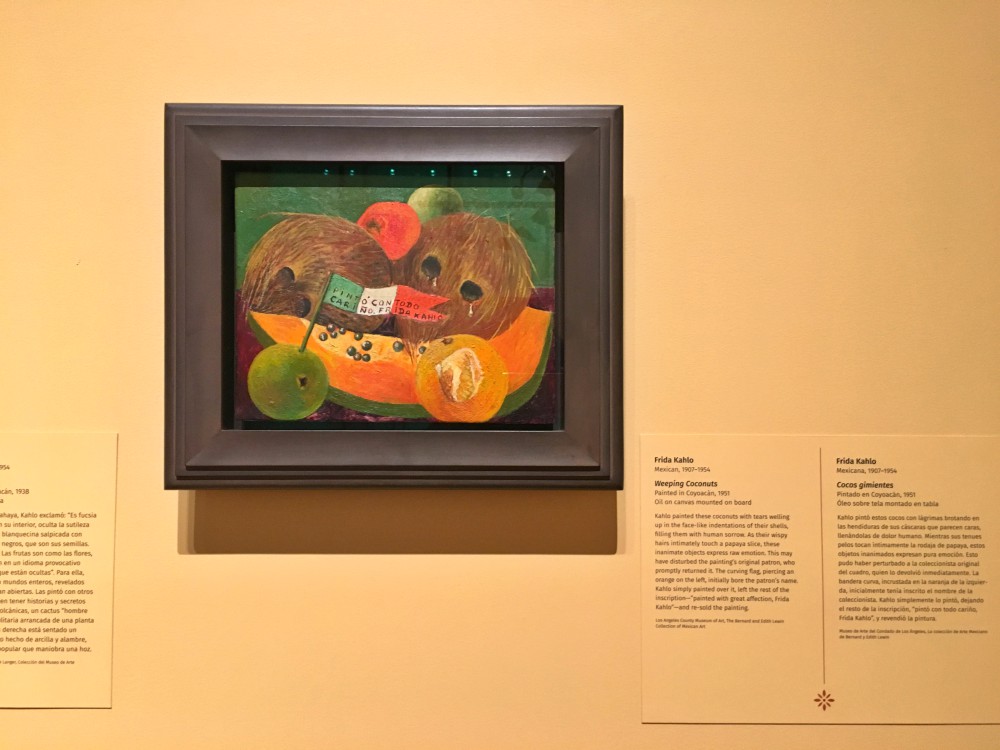

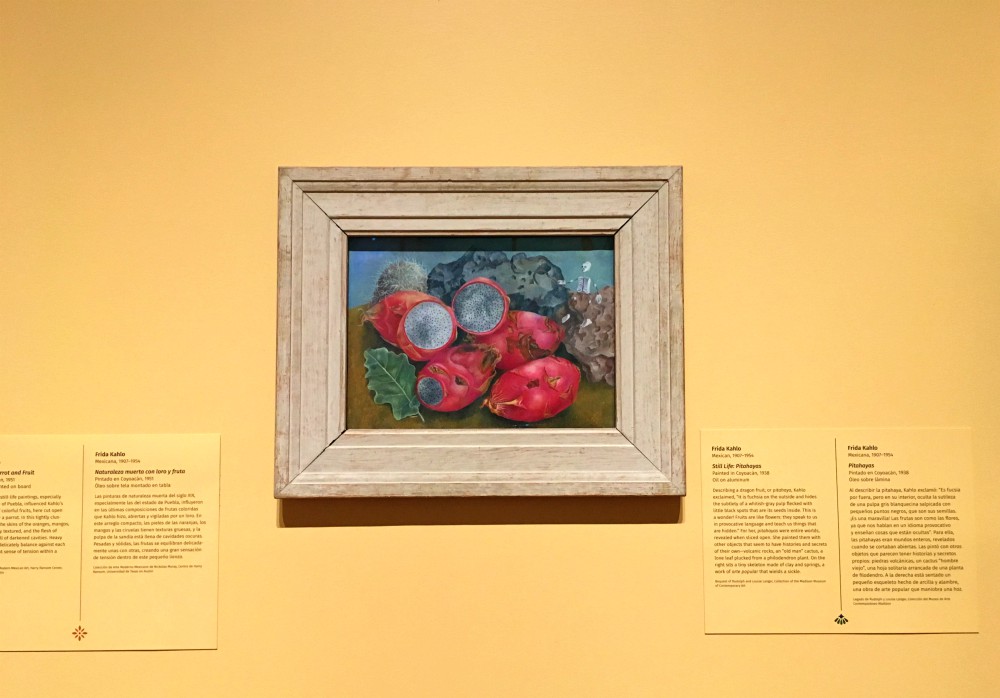

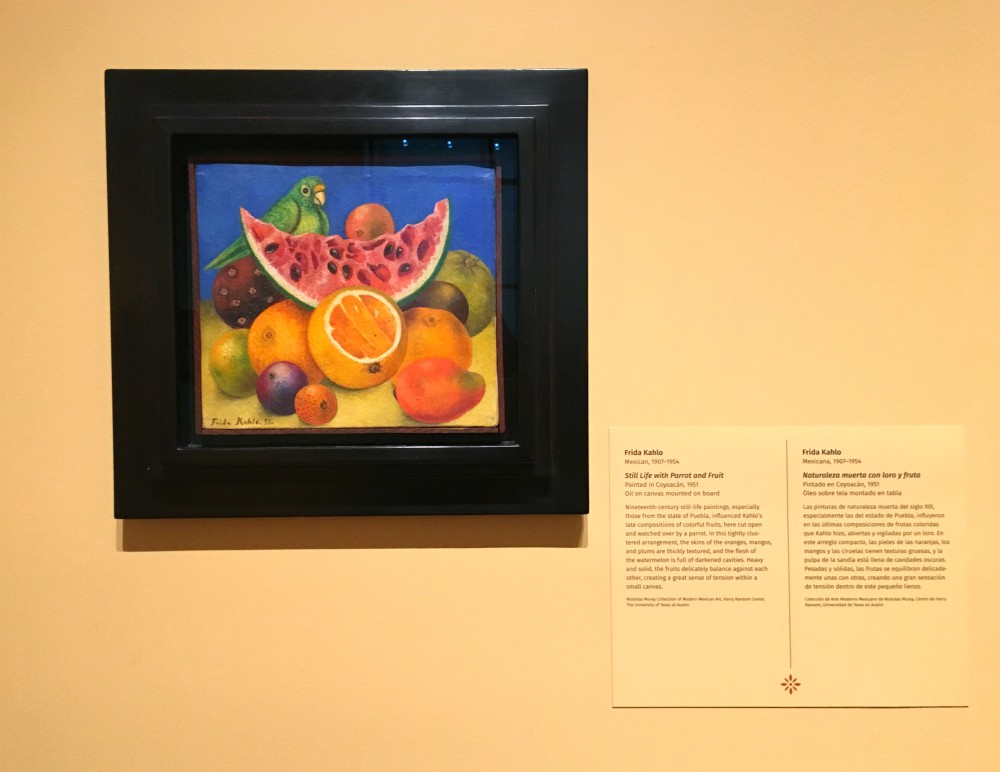

Still Life with Parrot and Fruit, 1951

Still Life with Parrot and Fruit, 1951

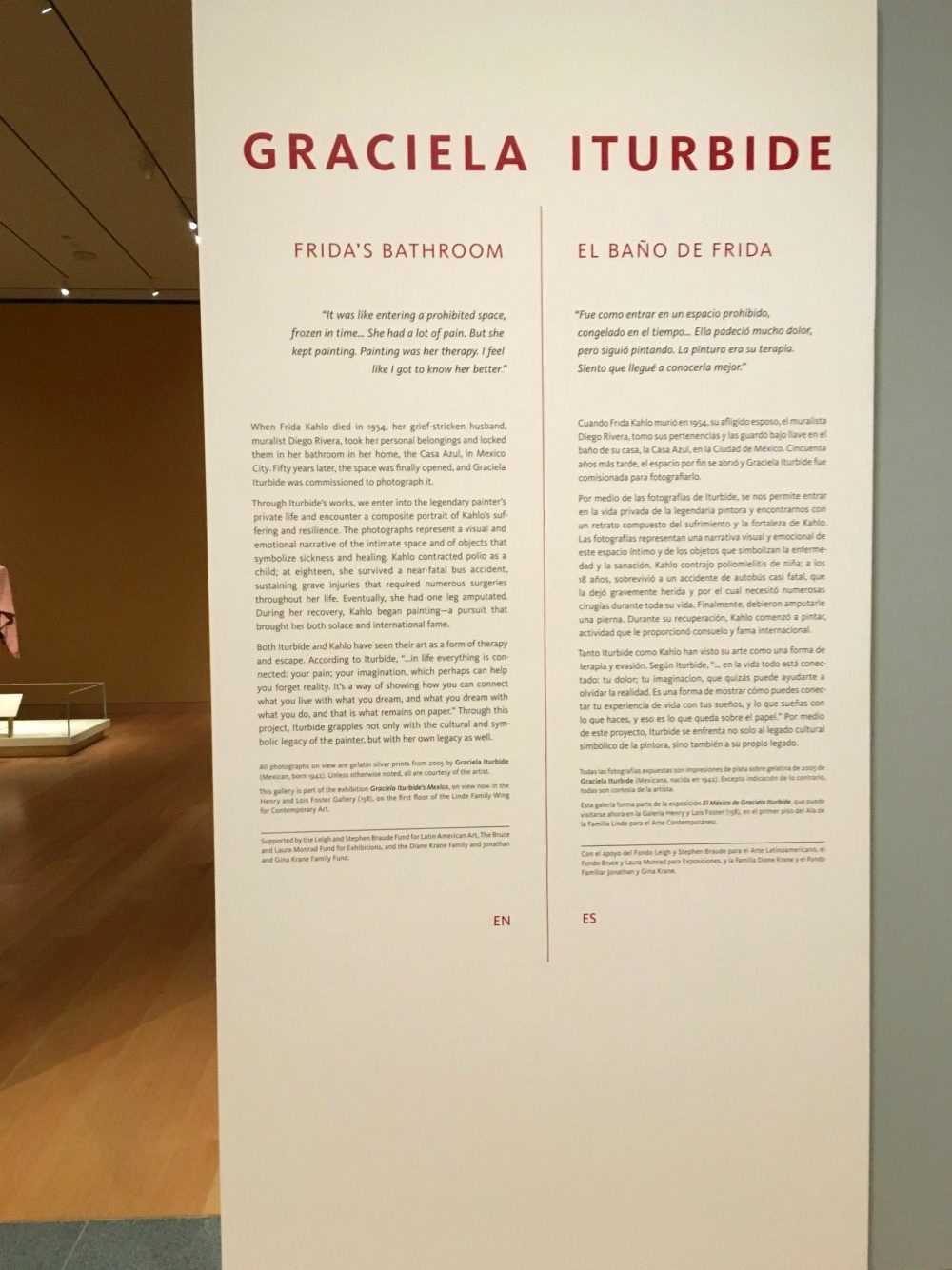

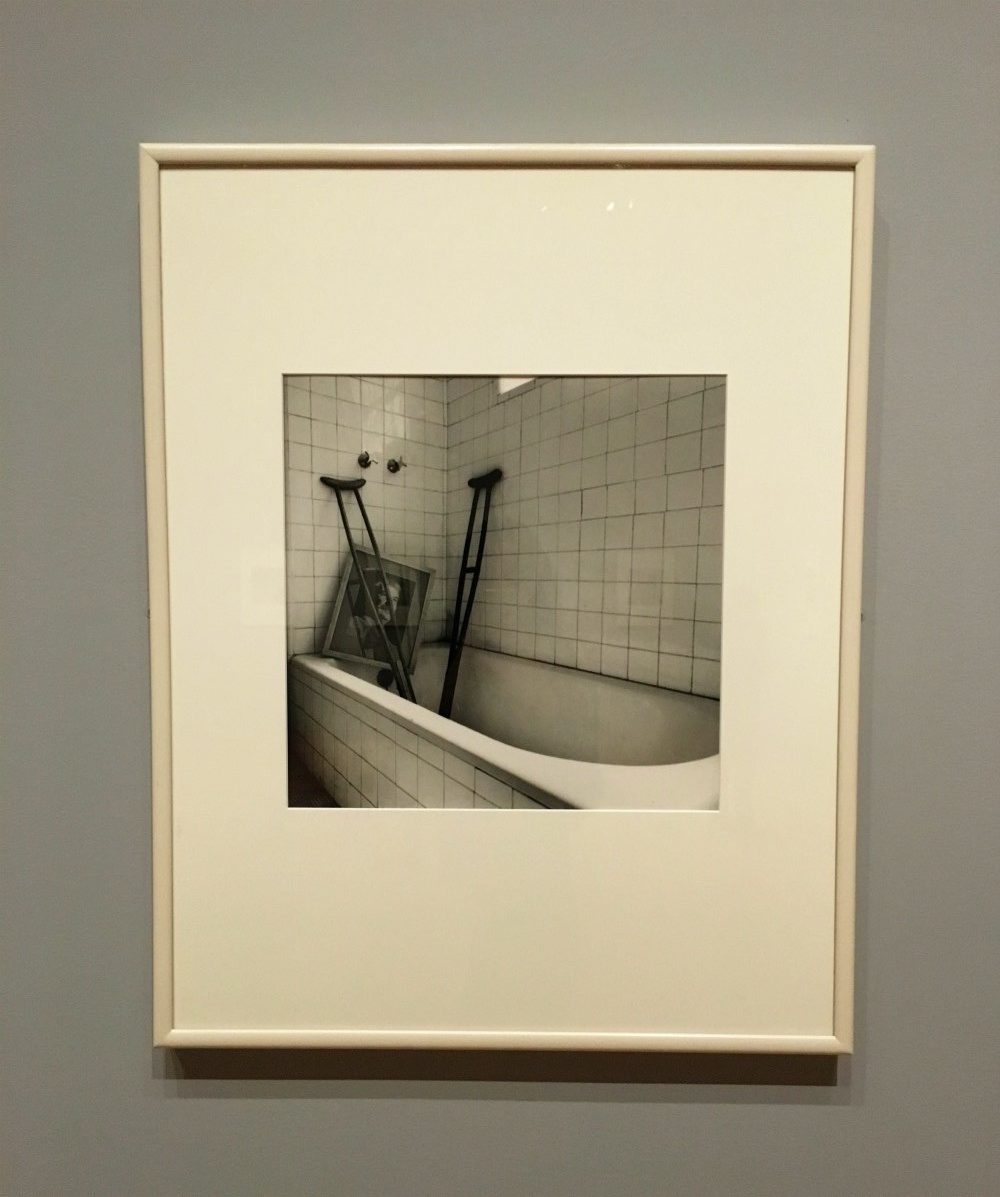

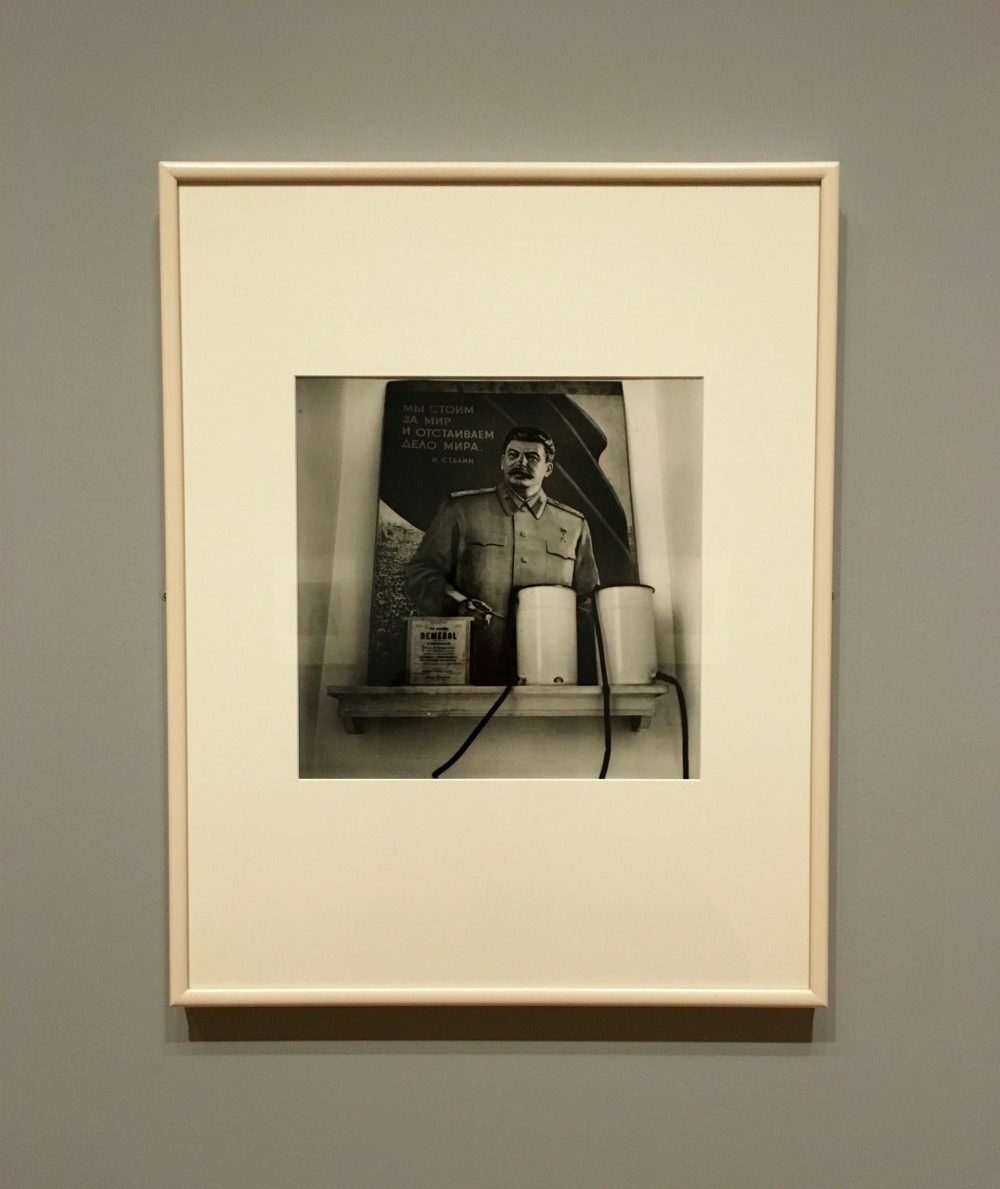

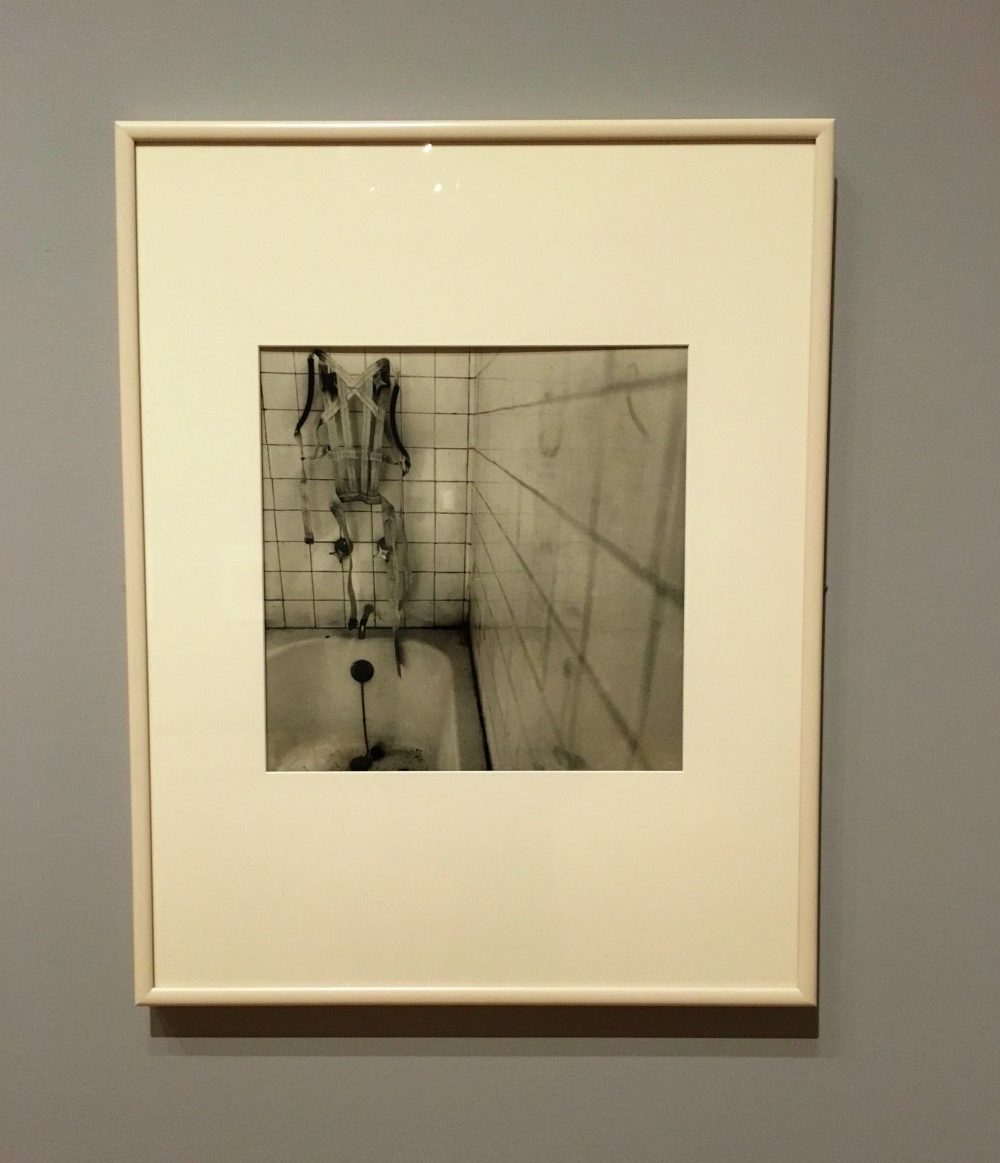

Kahlo's collections aren't simply given a second life in this exhibit, but a third — through the amazing photographs of contemporary artist Graciela Iturbide.

After Kahlo died in 1954, her husband, the legendary modern artist Diego Rivera, took her personal belongings and locked them in a bathroom.

The room wasn't opened until 50 years after Kahlo's death, when Iturbide photographed the items within.

They are haunting reminders of the difficult, depressing life Frida endured.

But if you're like me and love Frida, they aren't shocking and are actually comforting in their truth — as though you're one step closer to her.

I very clearly have a deep appreciation and love for this complex artist, and artist I have carried with me most of my life ever since my dad took me to a special exhibit on her at the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

I was probably a bit young to hear the 'unabridged' version of her life through the audio guide while taking in her difficult paintings — but it created a love for her that I'll always have with me.

Her paintings offer a reminder of the precariousness of life — it is unfair and tragic, but warm, beautiful and vivid.